MIT6.S081(6)-System Call Entry/Exit

Today: user -> kernel transition system calls, faults, interrupts enter the kernel in the same way important for isolation and performance lots of careful design and important detail

What needs to happen when a program makes a system call, e.g. write()? [CPU | user/kernel diagram] CPU resources are set up for user execution (not kernel) 32 registers, sp, pc, privilege mode, satp, stvec, sepc, … what needs to happen? save 32 user registers and pc switch to supervisor mode switch to kernel page table switch to kernel stack jump to kernel C code high-level goals don’t let user code interfere with user->kernel transition e.g. don’t execute user code in supervisor mode! transparent to user code – resume without disturbing

Today we’re focusing on the user/kernel transition and ignoring what the system call implemenation does once in the kernel but the sys call impl has to be careful and secure also!

What does the CPU’s “mode” protect? i.e. what does switching mode from user to supervisor allow? supervisor can use CPU control registers: satp – page table physical address stvec – ecall jumps here in kernel; points to trampoline sepc – ecall saves user pc here sscratch – address of trapframe supervisor can use PTEs that have no PTE_U flag but supervisor has no other powers! e.g. can’t use addresses that aren’t the in page table so kernel has to carefully set things up so it can work

preview: write() write() returns User

uservec() in trampoline.S userret() in trampoline.S Kernel usertrap() in trap.c usertrapret() in trap.c syscall() in syscall.c ^ sys_write() in sysfile.c —|

let’s watch an xv6 system call entering/leaving the kernel xv6 shell writing its $ prompt sh.c line 137: write(2, “$ “, 2); user/usys.S line 29 this is the write() function, still in user space a7 tells the kernel what system call we want – SYS_write = 16 ecall – triggers the user/kernel transition

let’s start by putting a breakpoint on the ecall user/sh.asm says write()’s ecall is at address 0xde6

$ make qemu-gdb (gdb) b *0xde6 (gdb) c (gdb) delete 1 (gdb) x/3i 0xde4

let’s look at the registers (gdb) print $pc (gdb) info reg

$pc and $sp are at low addresses – user memory starts at zero C on RISC-V puts function arguments in a0, a1, a2, &c write() arguments: a0 is fd, a1 is buf, a2 is n

(gdb) x/2c $a1

the shell is printing the $ prompt

what page table is in use? (gdb) print/x $satp not very useful qemu: control-a c, info mem there are mappings for six pages instructions, data, stack guard (no PTE_U), stack, then two high mystery pages: trapframe and trampoline there are no mappings for kernel memory, devices, physical mem

let’s execute the ecall

(gdb) stepi

where are we? (gdb) print $pc we’re executing at a very high virtual address (gdb) x/6i 0x3ffffff000 these are the instructions we’re about to execute see uservec in kernel/trampoline.S it’s the start of the kernel’s trap handling code (gdb) info reg the registers hold user values (except $pc) qemu: info mem we’re still using the user page table note that $pc is in the trampoline page, the very last page

we’re executing in the “trampoline” page, which contains the start of the kernel’s trap handling code. ecall doesn’t switch page tables, so these kernel instructions have to exist somewhere in the user page table. the trampoline page is the answer: the kernel maps it at the top of every user page table. the kernel sets $stvec to the trampoline page’s virtual address. the trampoline is protected: no PTE_U flag.

(gdb) print/x $stvec

can we tell that we’re in supervisor mode? I don’t know a way to find the mode directly but observe $pc is executing in a page with no PTE_U flag lack of crash implies we are in supervisor mode

how did we get here? ecall did three things: change mode from user to supervisor save $pc in $sepc (gdb) print/x $sepc jump to $stvec (i.e. set $pc to $stvec) the kernel previously set $stvec, before jumping to user space

note: ecall lets user code switch to supervisor mode but the kernel immediately gains control via $stvec so the user program itself can’t execute as supervisor

what needs to happen now? save the 32 user register values (for later transparent resume) switch to kernel page table set up stack for kernel C code jump to kernel C code

why didn’t the RISC-V designers have ecall do these things for us? ecall does as little as possible: to give O/S designers scope for very fast syscalls / faults / intrs maybe O/S can handle some traps w/o switching page tables maybe we can map BOTH user and kernel into a single page table so no page table switch required maybe some registers do not have to be saved maybe no stack is required for simple system calls

there have been many clever schemes invented for kernel entry! different amounts of work by CPU different strategies for handler s/w performance here is often super important

what are our options at this point for saving user registers? can we just write them somewhere convenient in physical memory? no, even supervisor mode is constrained to use the page table can we first set satp to the kernel page table? supervisor mode is allowed to set satp… but we don’t know the address of the kernel page table at this point! and we need a free register to even execute csrw satp, $xx

two parts to the solution for where to save the 32 user registers:

- xv6 maps a 2nd kernel page, the trapframe, into every user page table it has space to hold the saved registers the kernel gives each process a different trapframe page the page at 0x3fffffe000 is the trapframe page see struct trapframe in kernel/proc.h (but we still need a register holding the trapframe’s address…)

- RISC-V provides the sscratch register the kernel puts a pointer to the trapframe in sscratch before entering user space supervisor code can swap any register with sscratch thus both getting hold of the value in sscratch, and simultaneously saving the register’s user value

see this at the start of uservec in trapframe.S: csrrw a0, sscratch, a0

the csrrw has already been executed due to some gdb quirk…

(gdb) print/x $a0 address of the trapframe (gdb> print/x $sscratch 0x2, the old first argument (fd)

now uservec() has 32 saves of user registers to the trapframe, via a0 so they can be restored later, when the system call returns let’s skip them

(gdb) b *0x3ffffff076 (gdb) c

now we’re setting up to be able to run C code in the kernel first a stack previously, kernel put a pointer to top of this process’s kernel stack in trapframe look at struct trapframe in kernel/proc.h “ld sp, 8(a0)” fetches the kernel stack pointer remember a0 points to the trapframe at this point the only kernel data the code can get at is the trapframe, so everything has to be loaded from there.

(gdb) stepi

retrieve hart ID into tp

(gdb) stepi

we want to jump to the kernel C function usertrap(), which the kernel previously saved in the trapframe. “ld t0, 16(a0)” fetches it into t0, we’ll use it in a moment, after switching to the kernel page table

(gdb) stepi

load a pointer to the kernel pagetable from the trapframe, and load it into satp, and issue an sfence to clear the TLB.

(gdb) stepi (gdb) stepi (gdb) stepi

why isn’t there a crash at this point? after all we just switched page tables while executing! answer: the trampoline page is mapped at the same virtual address in the kernel page table as well as every user page table

(gdb) print $pc qemu: info mem

with the kernel page table we can now use kernel functions and data

the jr t0 is a jump to usertrap() (using t0 retrieved from trapframe)

(gdb) print/x $t0 (gdb) x/4i $t0 (gdb) stepi (gdb) tui enable

we’re now in usertrap() in kernel/trap.c various traps come here, e.g. errors, device interrupts, and system calls usertrap() looks in the scause register to see the trap cause see Figure 10.3 on page 102 of The RISC-V Reader scause = 8 is a system call

(gdb) next … until syscall() (gdb) step (gdb) next

now we’re in syscall() kernel/syscall.c myproc() uses tp to retrieve current struct proc * p->xxx is usually a slot in the current process’s struct proc

syscall() retrieves the system call number from saved register a7 p->trapframe points to the trapframe, with saved registers p->trapframe->a7 holds 16, SYS_write p->trapframe->a0 holds write() first argument – fd p->trapframe->a1 holds buf p->trapframe->a2 holds n

(gdb) next … (gdb) print num

then dispatches through syscall[num], a table of functions

(gdb) next … (gdb) step

aha, we’re in sys_write. at this point system call implementations are fairly ordinary C code. let’s skip to the end, to see how a system call returns to user space.

(gdb) finish

notice that write() produced console output (the shell’s $ prompt) back to syscall() the p->tf->a0 assignment causes (eventually) a0 to hold the return value the C calling convention on RISC-V puts return values in a0

(gdb) next

back to usertrap()

(gdb) print p->trapframe->a0

write() returned 2 – two characters – $ and space

(gdb) next (gdb) step

now we’re in usertrapret(), which starts the process of returning to the user program

we need to prepare for the next user->kernel transition stvec = uservec (the trampoline), for the next ecall traframe satp = kernel page table, for next uservec traframe sp = top of kernel stack trapframe trap = usertrap trapframe hartid = hartid (in tp)

at the end, we’ll use the RISC-V sret instruction we need to prepare a few registers that sret uses sstatus – set the “previous mode” bit to user sepc – the saved user program counter (from trap entry)

we’re going to switch to the user page table while executing not OK in usertrapret(), since it’s not mapped in the user page table. need a page that’s mapped in both user and kernel page table – the trampoline. jump to userret in trampoline.S

(gdb) tui disable (gdb) step (gdb) x/8i 0x3ffffff090

a0 holds TRAPFRAME a1 holds user page table address the csrw satp switches to the user address space

(gdb) stepi (gdb) stepi (gdb) stepi

the csrw scratch puts the user a0 into sscratch just before sret we’ll do a swap, so that a0 holds the user a0 and sscratch holds trapframe pointer. which is what uservec expects.

now 32 loads from the trapframe into registers these restore the user registers let’s skip over them

(gdb) b *0x3ffffff10a (gdb) c

here’s the csrw that swaps a0 with sscratch

(gdb) stepi (gdb) print/x $a0 – the return value from write() (gdb) print/x $sscratch – trapframe address for uservec

now we’re at the sret instruction

(gdb) print $pc (gdb) stepi (gdb) print $pc

now we’re back in the user program ($pc = 0x0xdea) returning 2 from the write() function

(gdb) print/x $a0

and we’re done with a system call!

summary system call entry/exit is far more complex than function call much of the complexity is due to the requirement for isolation and the desire for simple and fast hardware mechanisms a few design questions to ponder: can an evil program abuse the entry mechanism? can you think of ways to make the hardware or software simpler? can you think of ways to make traps faster?

Lab: traps

RISC-V assembly (easy)

Which registers contain arguments to functions? For example, which register holds 13 in main’s call to printf?

13 -> a2

12 -> a1

第一个参数-> a0 在printf中代表格式化字符串的地址,在exit(0)中代表参数0

ra(返回地址)

s0(保存帧指针)

auipc xx, 0x0 通过将当前PC的高20位加上一个立即数(在这个例子中是0x0,表示没有偏移)来形成一个高地址部分。这个结果会存储在目标寄存器 xx 中。

Where is the call to function f in the assembly code for main? Where is the call to g? (Hint: the compiler may inline functions.)

printf("%d %d\n", f(8)+1, 13);

24: 4635 li a2,13

26: 45b1 li a1,12

这里直接将计算后的值写入到寄存器中,通过内联的方式调用函数。

At what address is the function printf located?

34: 600080e7 jalr 1536(ra) # 630 <printf>

$0x630$ 位置

What value is in the register ra just after the jalr to printf in main?

30: 00000097 auipc ra,0x0

34: 600080e7 jalr 1536(ra) # 630 <printf>

$0x630 = 0x30(ra) + 1536, ra = 0x30$

Run the following code.

unsigned int i = 0x00646c72;

printf("H%x Wo%s", 57616, &i);

输出 : He110 World

其中57616十六进制数组的ascii码为110

因为 RISC-V 是 little-endian. 内存中存储i为逆序的,所以会倒序 :

-

0x72(ASCII ‘r’) -

0x6c(ASCII ’l') -

0x64(ASCII ’d') -

0x00(null terminator)

In the following code, what is going to be printed after 'y='? (note: the answer is not a specific value.) Why does this happen?

printf("x=%d y=%d", 3);

因为printf会尝试从栈或者内存上读取这个缺失的参数,这会导致未定义的行为,可能会获取到任意的内存产生未知的值,具体取决于栈和内存的的状态,编译行为和优化,运行环境和内存的管理。

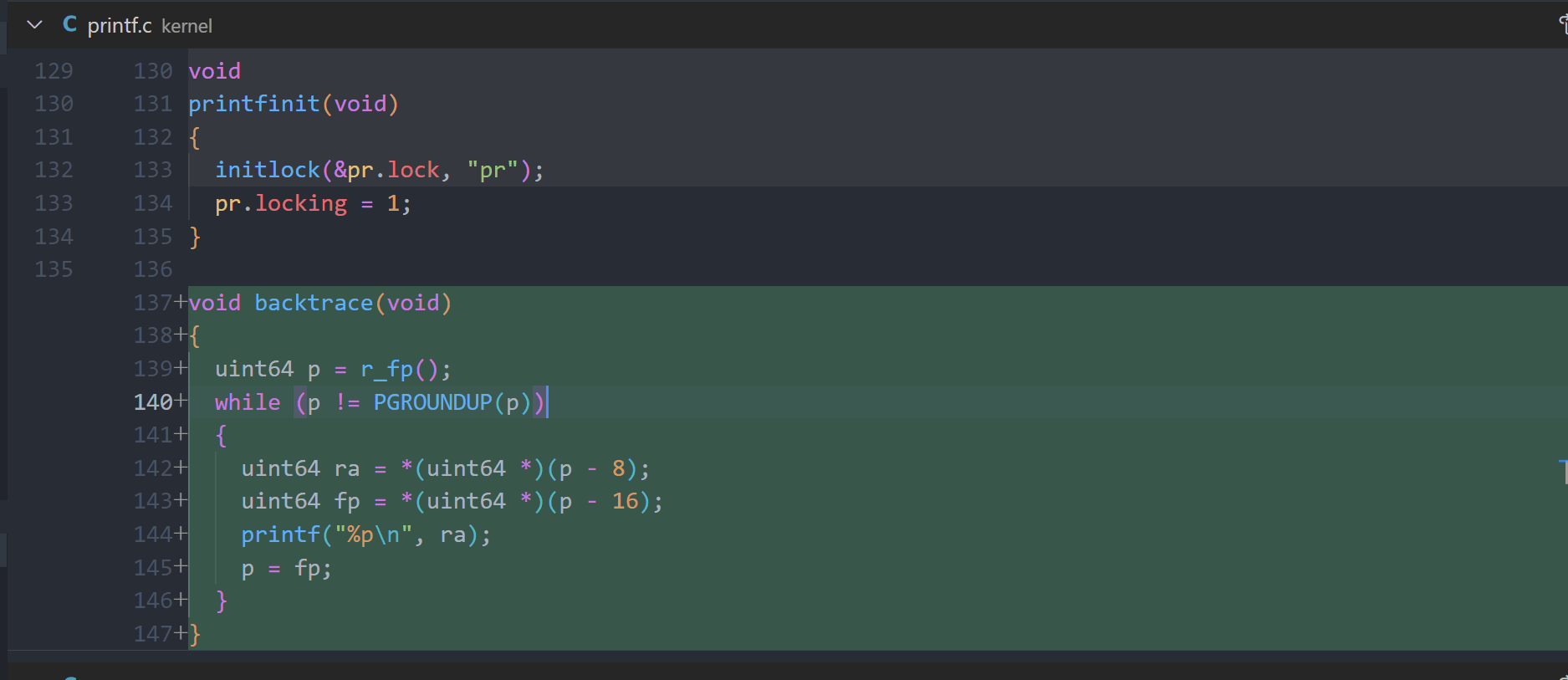

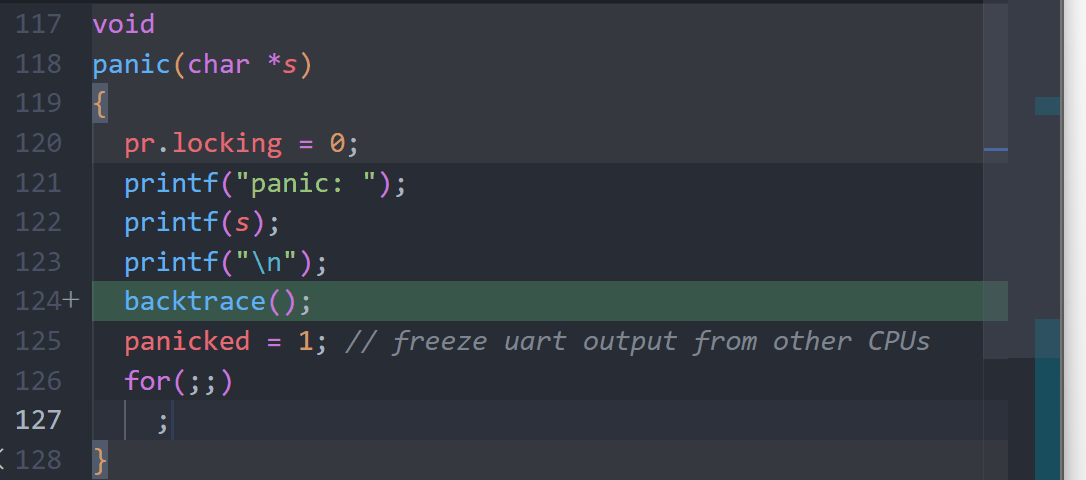

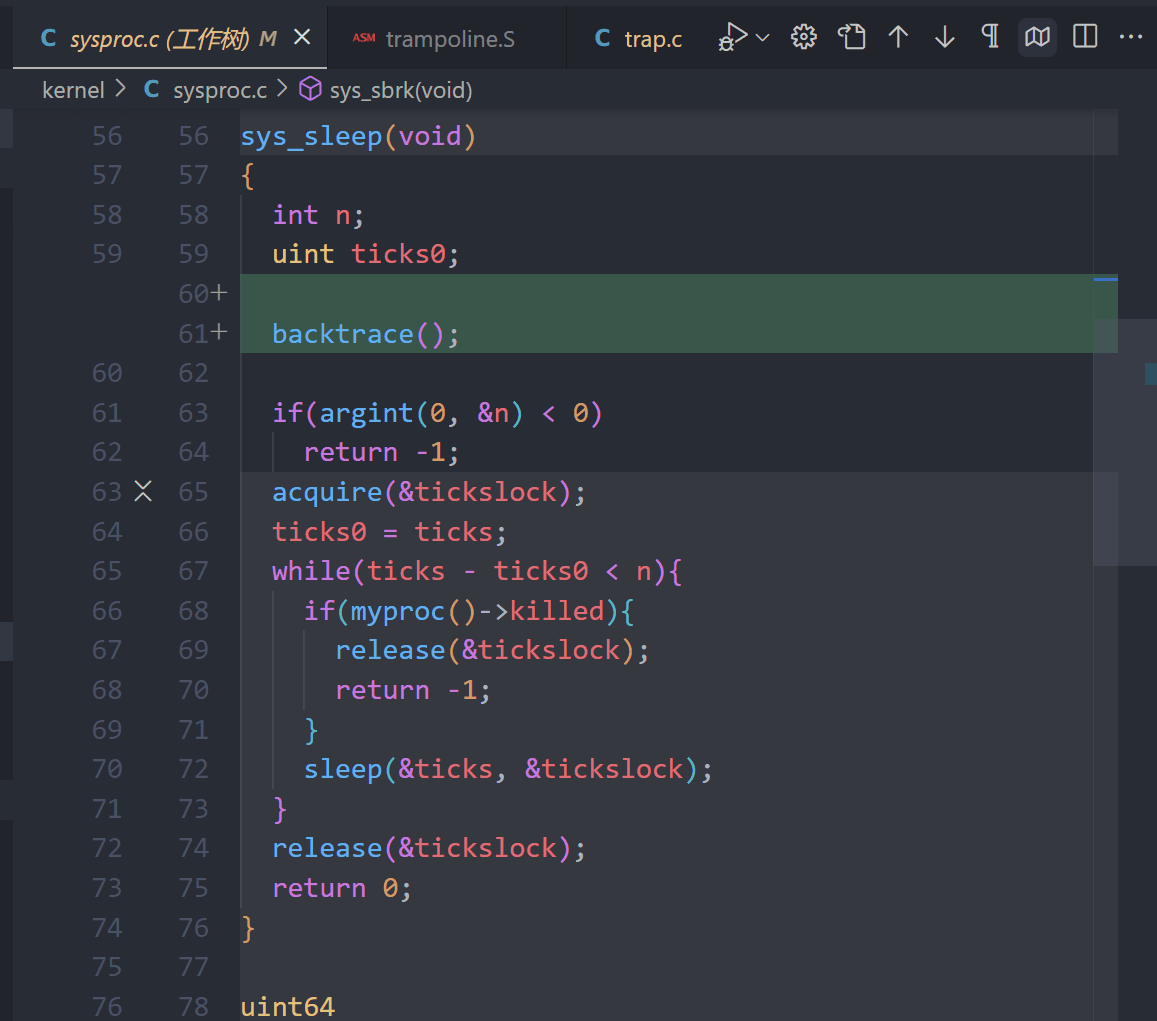

Backtrace (moderate)

defs.h

void backtrace(void);

printf.c

void backtrace(void)

{

uint64 p = r_fp();

while (p != PGROUNDUP(p))

{

uint64 ra = *(uint64 *)(p - 8);

uint64 fp = *(uint64 *)(p - 16);

printf("%p\n", ra);

p = fp;

}

}

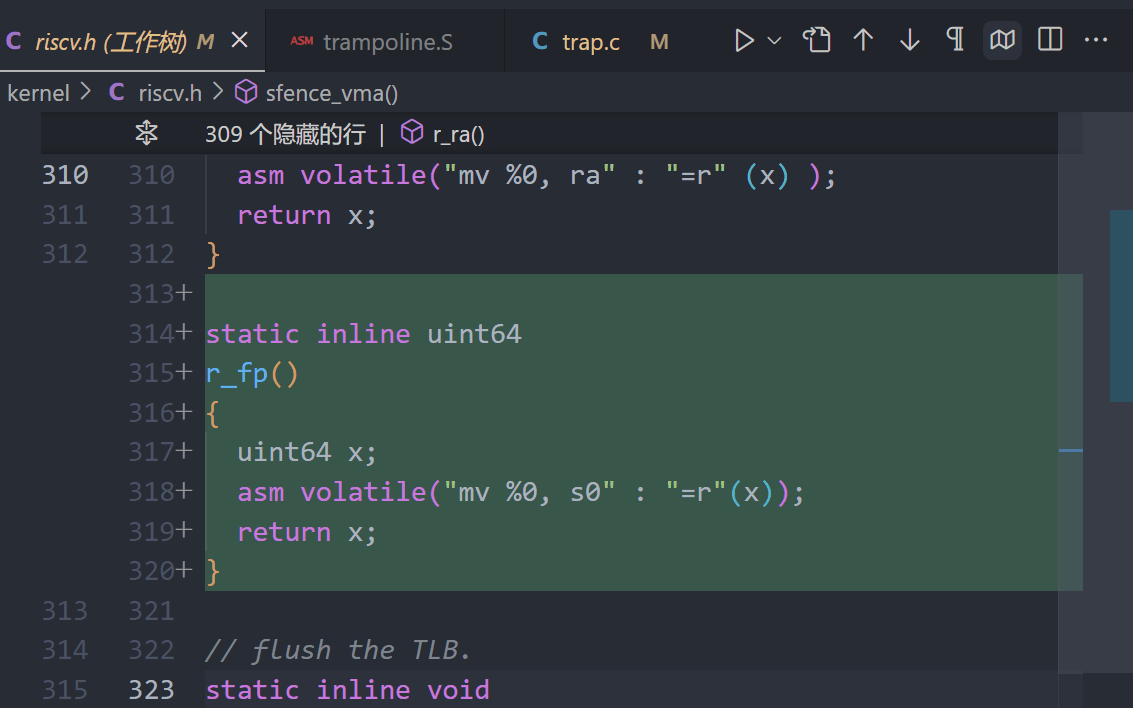

riscv.h

Alarm (hard)

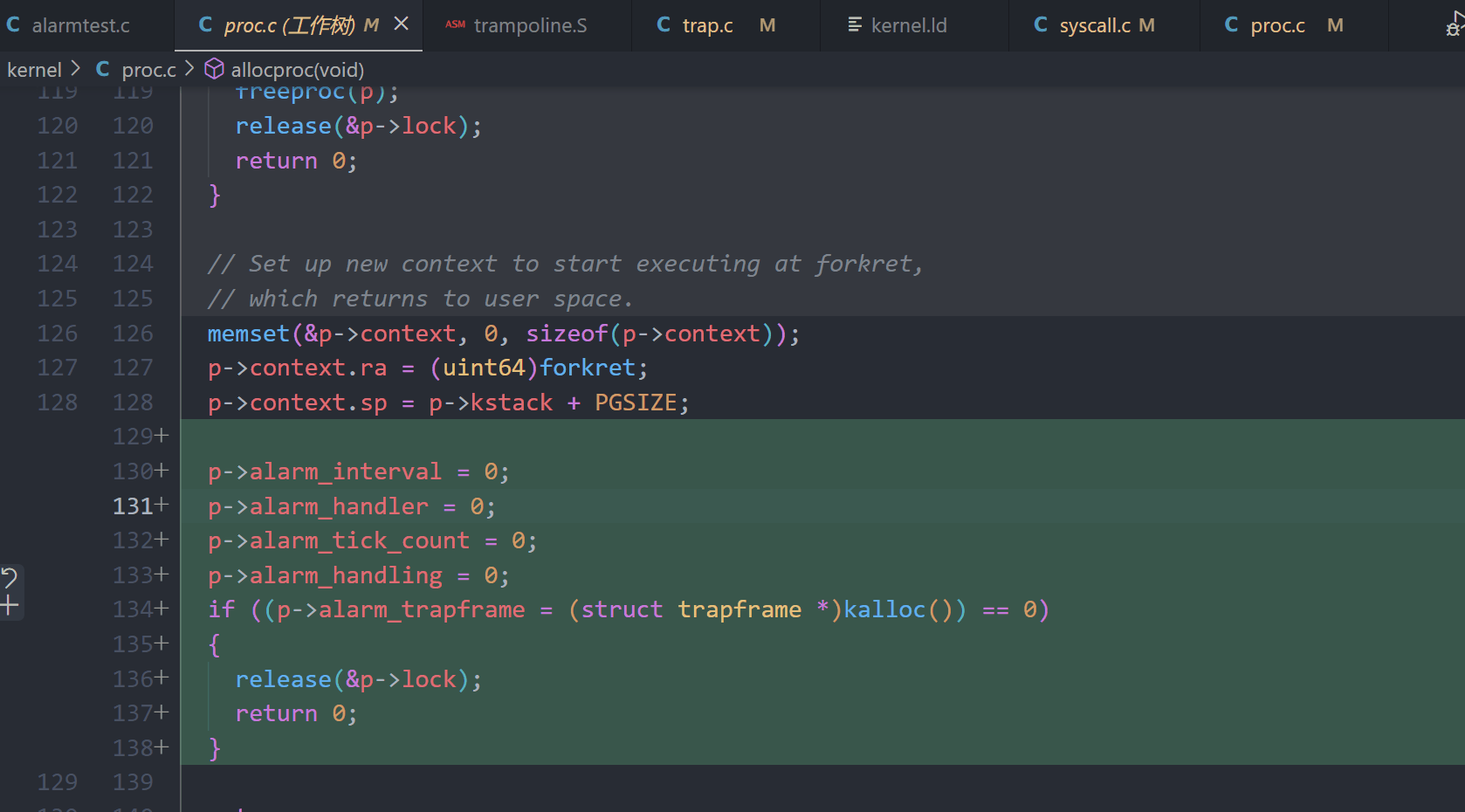

proc.c

p->alarm_interval = 0;

p->alarm_handler = 0;

p->alarm_tick_count = 0;

p->alarm_handling = 0;

if ((p->alarm_trapframe = (struct trapframe *)kalloc()) == 0)

{

release(&p->lock);

return 0;

}

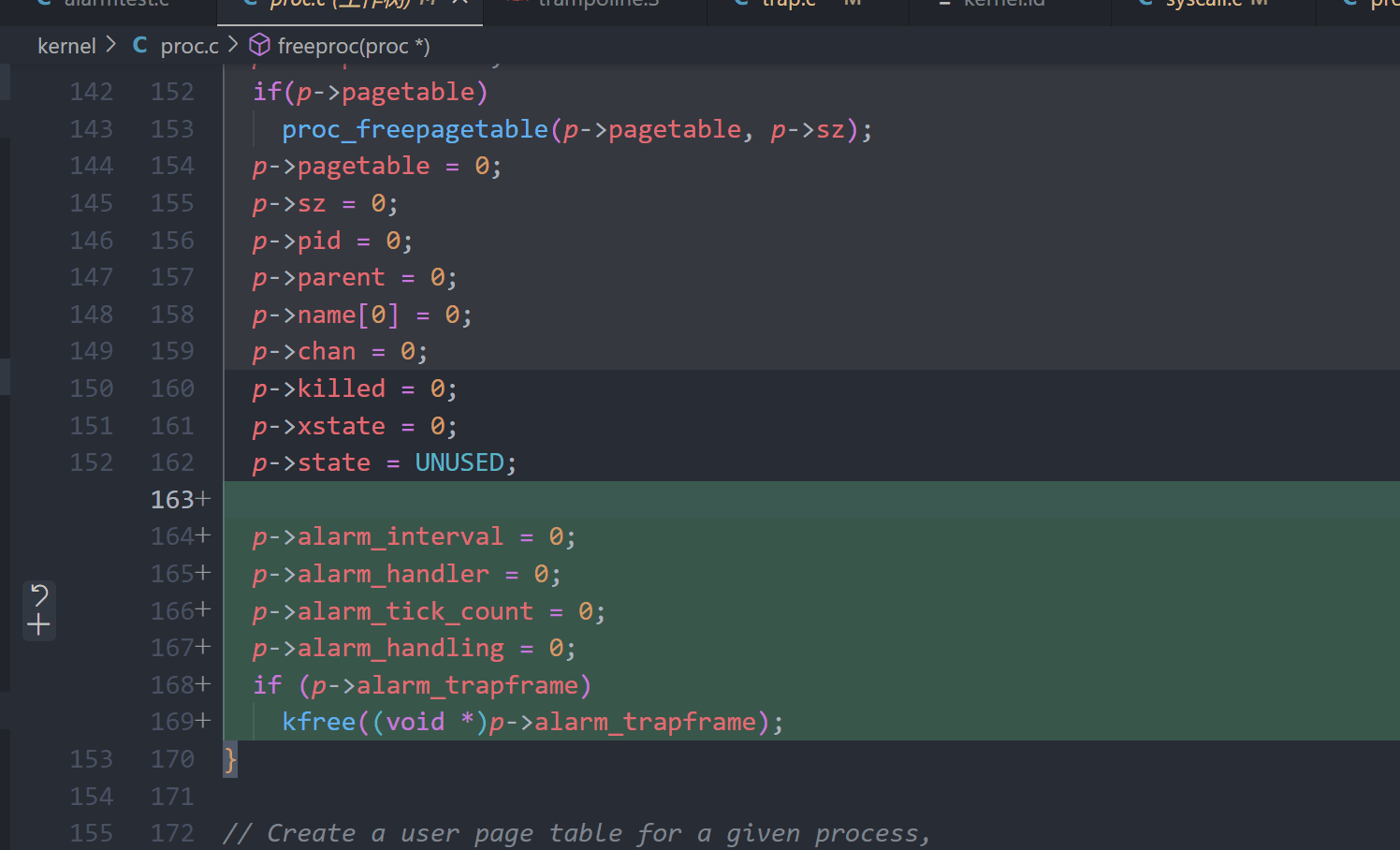

p->alarm_interval = 0;

p->alarm_handler = 0;

p->alarm_tick_count = 0;

p->alarm_handling = 0;

if (p->alarm_trapframe)

kfree((void *)p->alarm_trapframe);

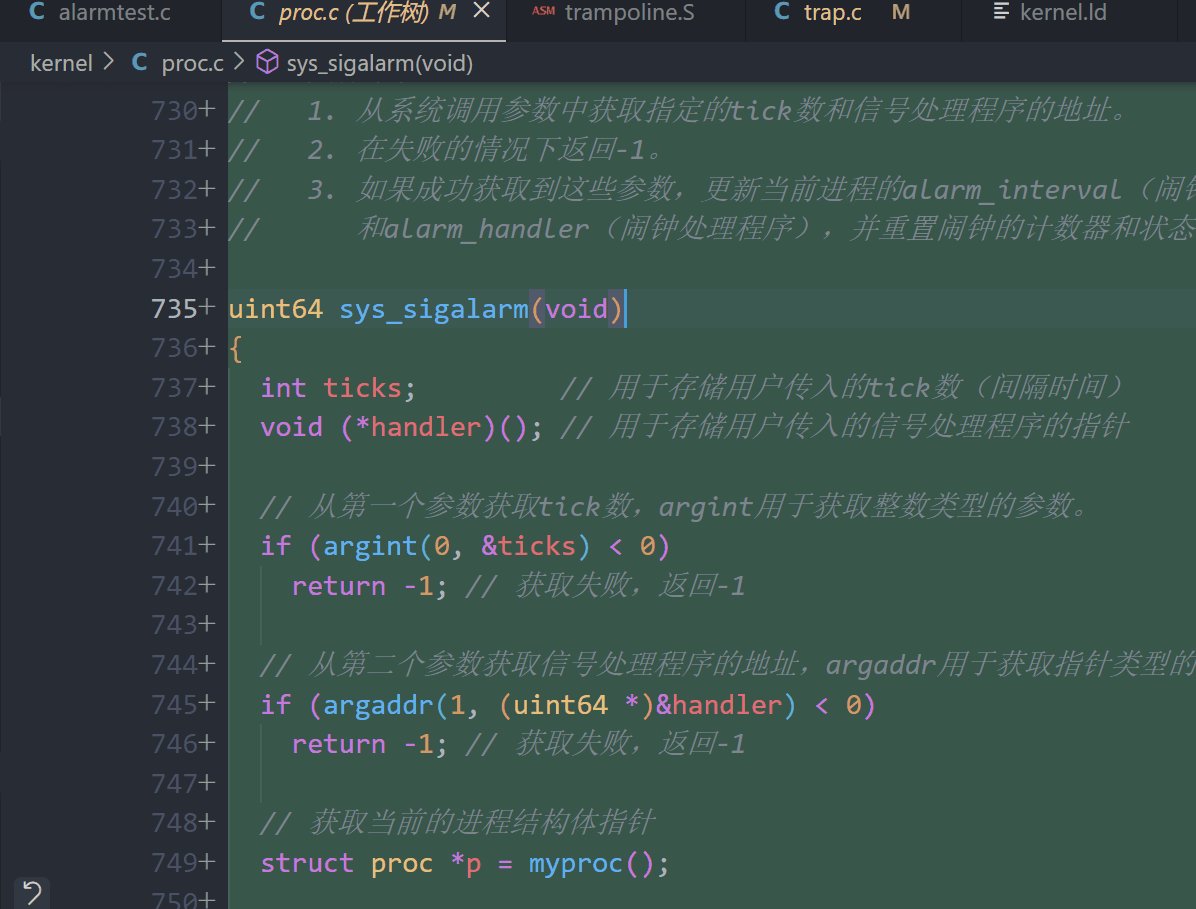

// sys_sigalarm - 系统调用,用于设置一个进程的定时闹钟信号处理程序

//

// 参数:

// 无直接参数。使用了argint()和argaddr()来从系统调用参数中提取值。

// 返回值:

// 成功返回0,失败返回-1。

//

// 功能:

// 该函数设置一个进程的定时闹钟,当计时器达到指定的tick数时,触发

// 用户定义的信号处理程序(handler)。

//

// 具体来说:

// 1. 从系统调用参数中获取指定的tick数和信号处理程序的地址。

// 2. 在失败的情况下返回-1。

// 3. 如果成功获取到这些参数,更新当前进程的alarm_interval(闹钟间隔)

// 和alarm_handler(闹钟处理程序),并重置闹钟的计数器和状态。

uint64 sys_sigalarm(void)

{

int ticks; // 用于存储用户传入的tick数(间隔时间)

void (*handler)(); // 用于存储用户传入的信号处理程序的指针

// 从第一个参数获取tick数,argint用于获取整数类型的参数。

if (argint(0, &ticks) < 0)

return -1; // 获取失败,返回-1

// 从第二个参数获取信号处理程序的地址,argaddr用于获取指针类型的参数。

if (argaddr(1, (uint64 *)&handler) < 0)

return -1; // 获取失败,返回-1

// 获取当前的进程结构体指针

struct proc *p = myproc();

// 设置进程的闹钟间隔

p->alarm_interval = ticks;

// 设置进程的信号处理程序

p->alarm_handler = handler;

// 重置闹钟的计数器

p->alarm_tick_count = 0;

// 初始化闹钟处理状态为未处理

p->alarm_handling = 0;

// 设置成功,返回0

return 0;

}

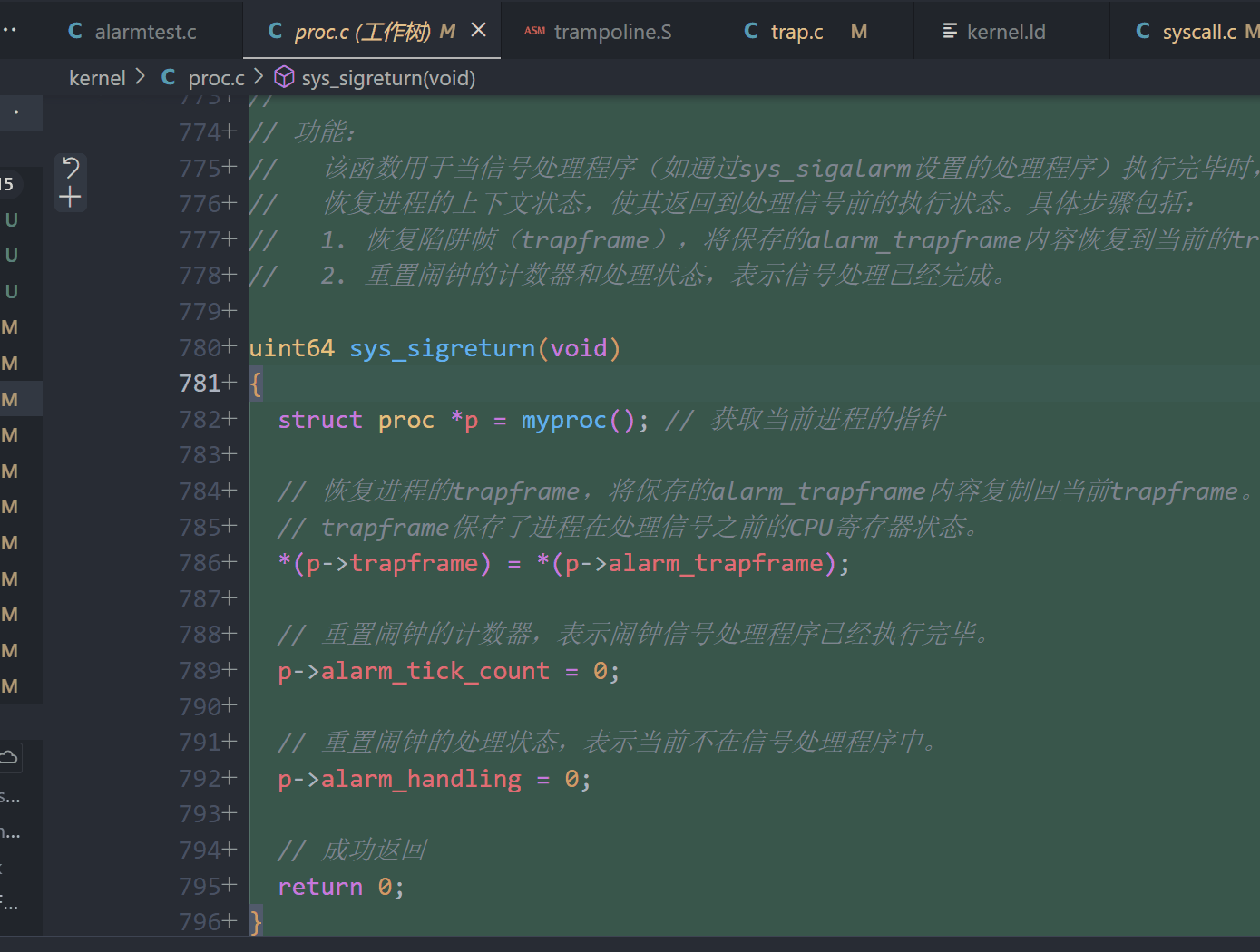

// sys_sigreturn - 系统调用,用于从信号处理程序返回到主程序

//

// 参数:

// 无直接参数。

// 返回值:

// 成功返回0。

//

// 功能:

// 该函数用于当信号处理程序(如通过sys_sigalarm设置的处理程序)执行完毕时,

// 恢复进程的上下文状态,使其返回到处理信号前的执行状态。具体步骤包括:

// 1. 恢复陷阱帧(trapframe),将保存的alarm_trapframe内容恢复到当前的trapframe中。

// 2. 重置闹钟的计数器和处理状态,表示信号处理已经完成。

uint64 sys_sigreturn(void)

{

struct proc *p = myproc(); // 获取当前进程的指针

// 恢复进程的trapframe,将保存的alarm_trapframe内容复制回当前trapframe。

// trapframe保存了进程在处理信号之前的CPU寄存器状态。

*(p->trapframe) = *(p->alarm_trapframe);

// 重置闹钟的计数器,表示闹钟信号处理程序已经执行完毕。

p->alarm_tick_count = 0;

// 重置闹钟的处理状态,表示当前不在信号处理程序中。

p->alarm_handling = 0;

// 成功返回

return 0;

}

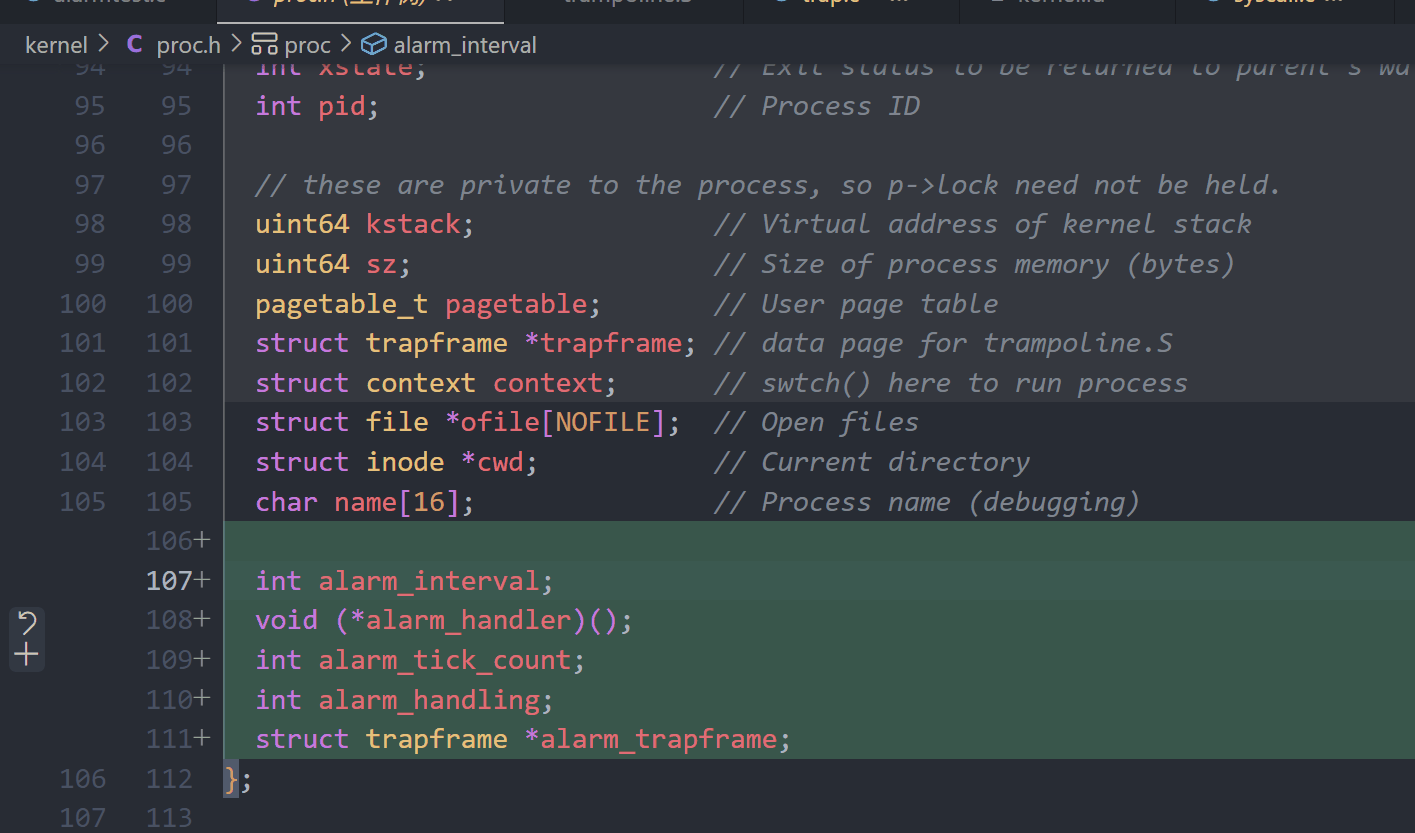

proc.h

int alarm_interval;

void (*alarm_handler)();

int alarm_tick_count;

int alarm_handling;

struct trapframe *alarm_trapframe;

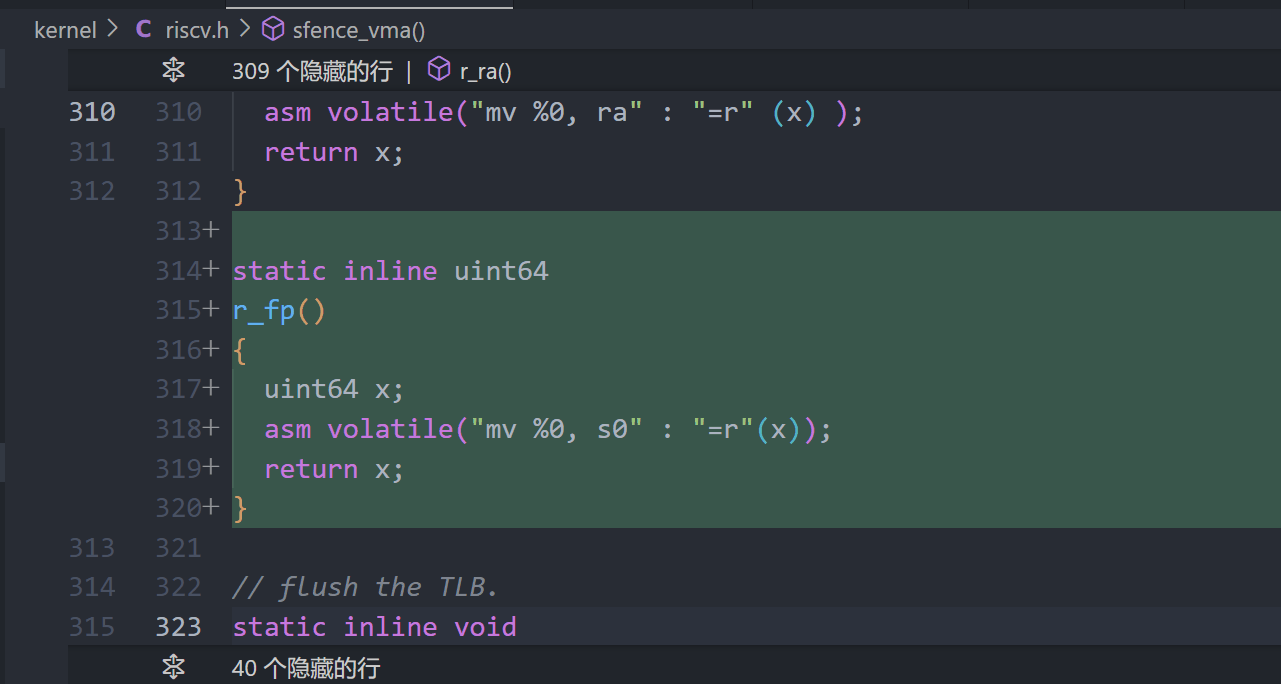

riscv.h

static inline uint64

r_fp()

{

uint64 x;

asm volatile("mv %0, s0" : "=r"(x));

return x;

}

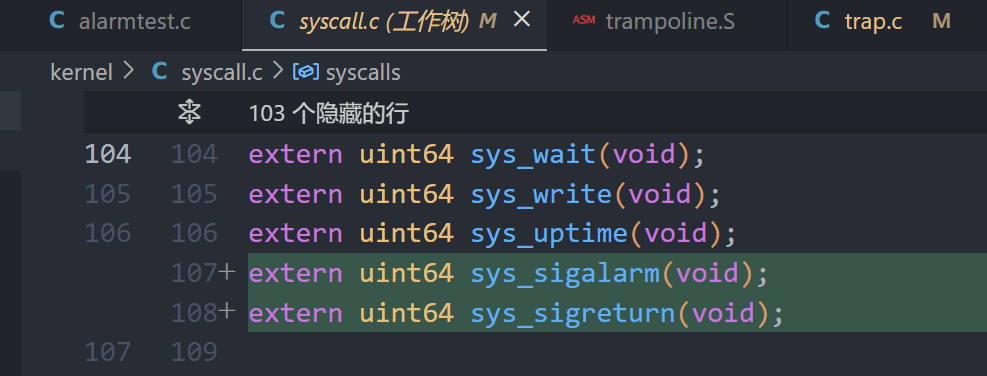

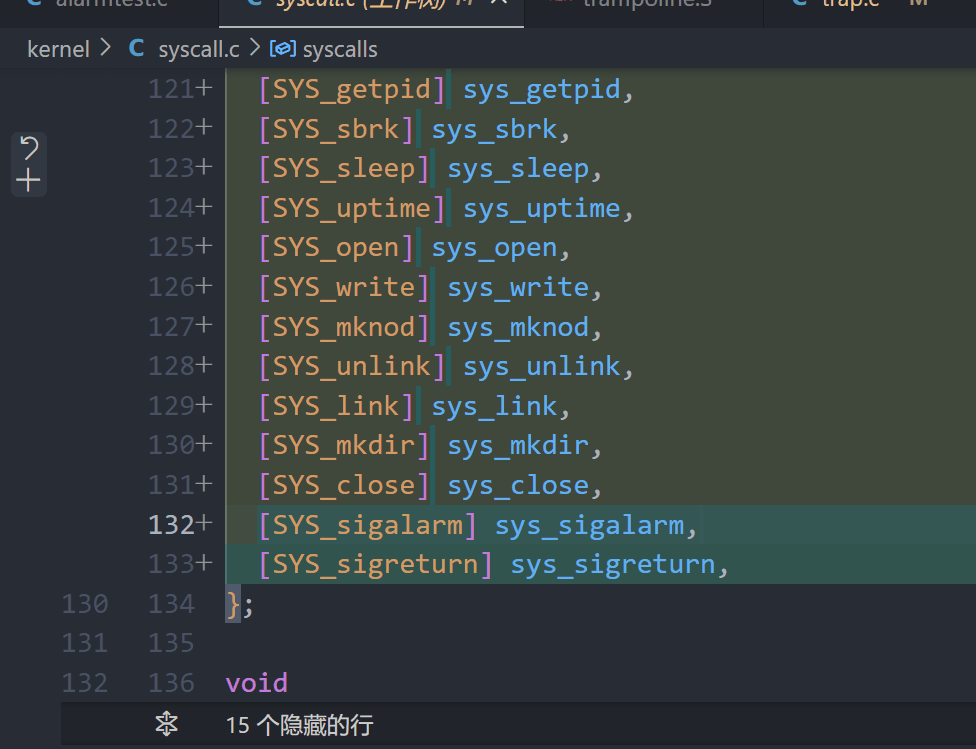

syscall.c

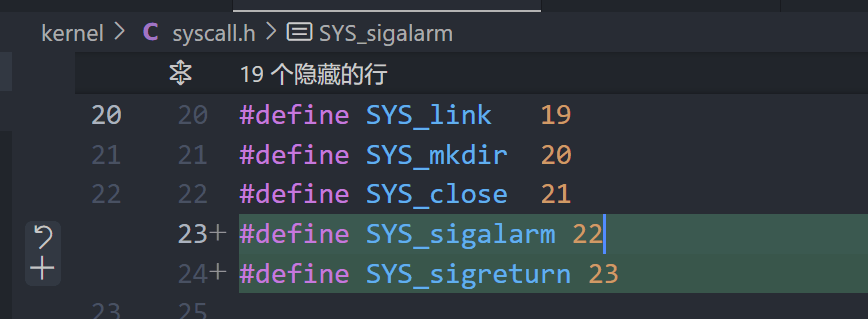

syscall.h

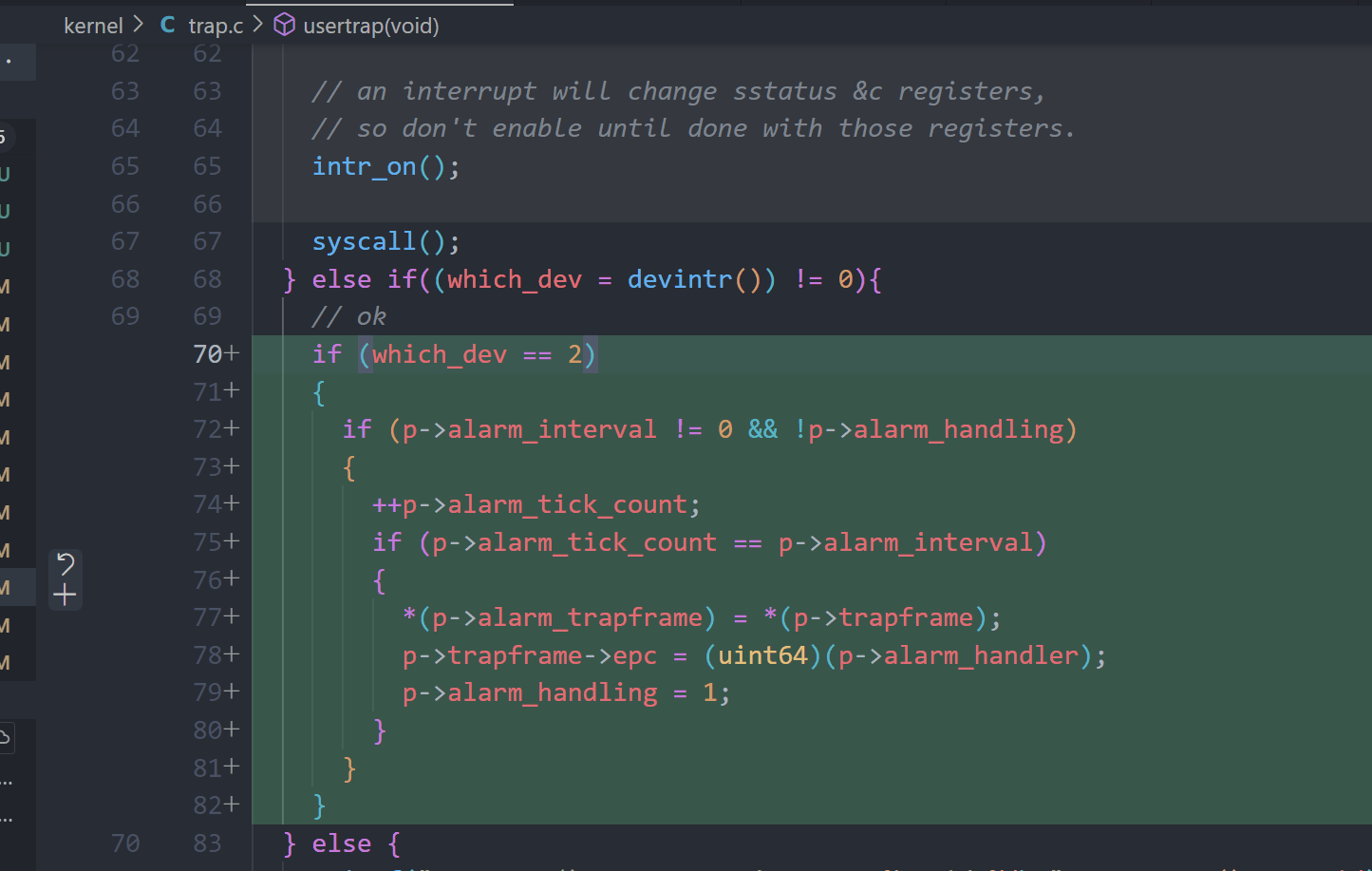

trap.c

// ok

if (which_dev == 2)

{

if (p->alarm_interval != 0 && !p->alarm_handling)

{

++p->alarm_tick_count;

if (p->alarm_tick_count == p->alarm_interval)

{

*(p->alarm_trapframe) = *(p->trapframe);

p->trapframe->epc = (uint64)(p->alarm_handler);

p->alarm_handling = 1;

}

}

}

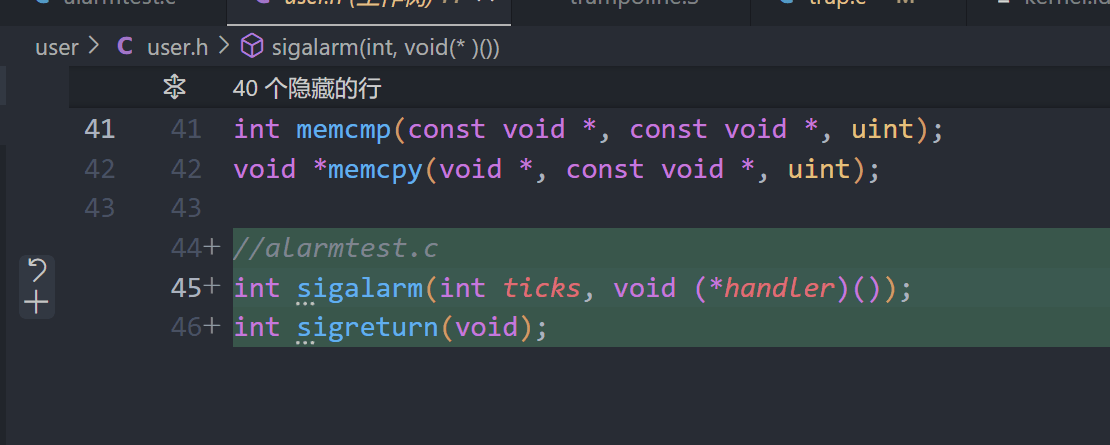

user.h

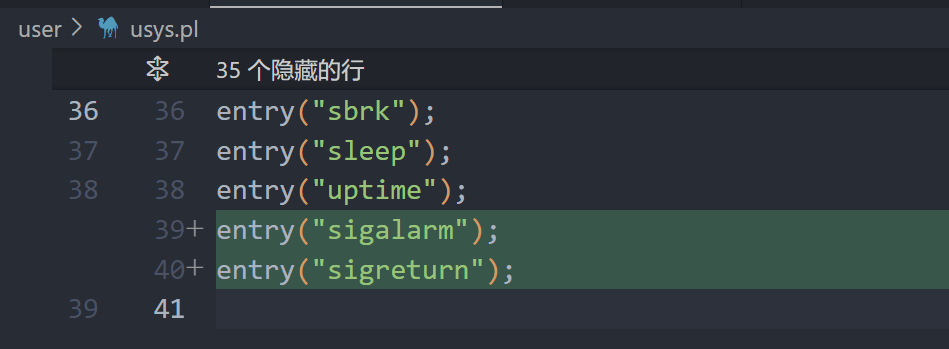

usys.pl