MIT6.S081(1)-O/S overview

Class Page

Overview

6.S081 goals

- Understand operating system (O/S) design and implementation

- Hands-on experience extending a small O/S

- Hands-on experience writing systems software

What is the purpose of an O/S?

- Abstract the hardware for convenience and portability

- Multiplex the hardware among many applications

- Isolate applications in order to contain bugs

- Allow sharing among cooperating applications

- Control sharing for security

- Don’t get in the way of high performance

- Support a wide range of applications

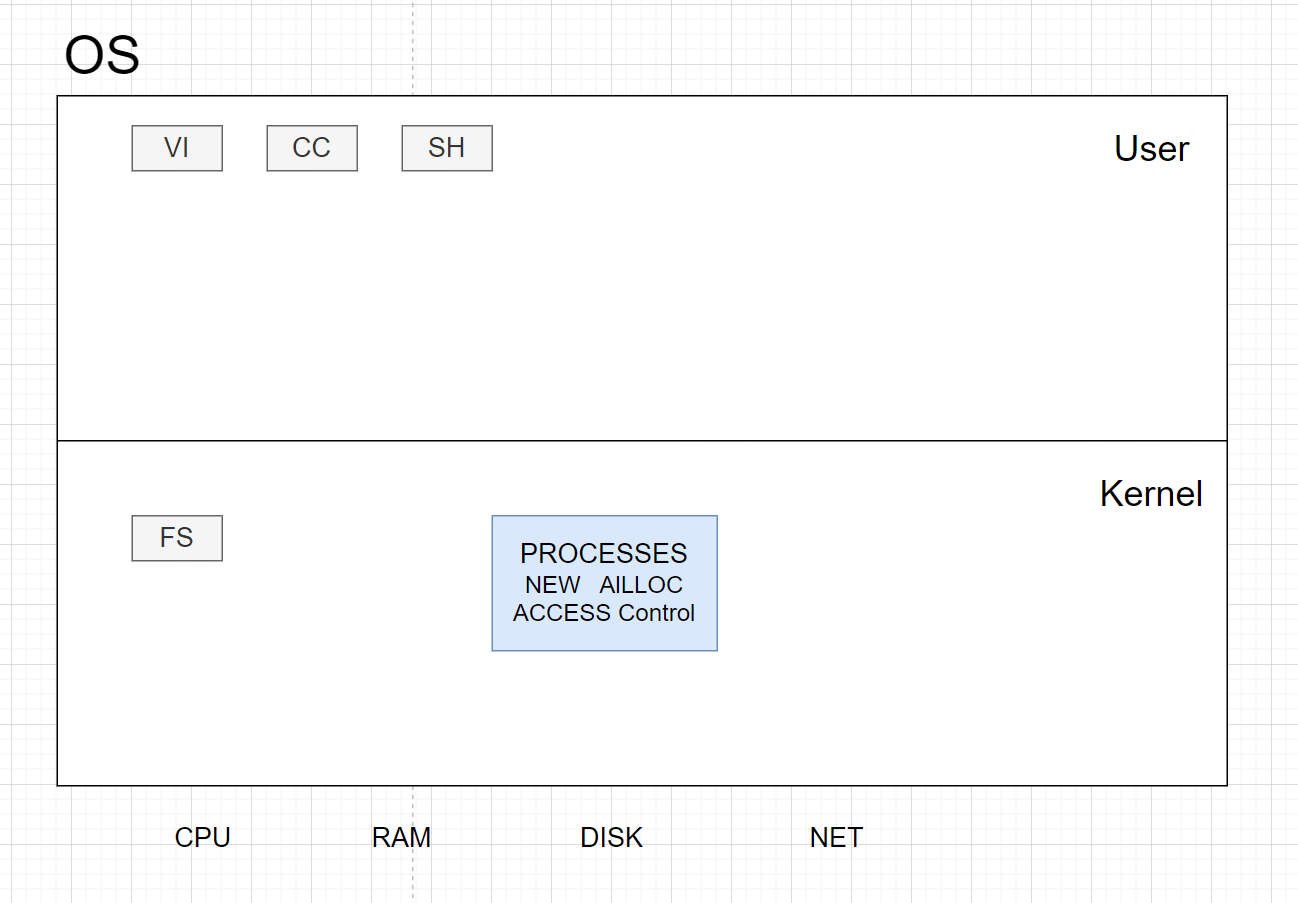

Organization: layered picture

- user applications:

vi,gcc,DB, &c - kernel services

- h/w:

CPU,RAM,disk,net, &c

- we care a lot about the interfaces and internal kernel structure

What services does an O/S kernel typically provide?

- process (a running program)

- memory allocation

- file contents

- file names, directories

- access control (security)

- many others: users, IPC(Inter-Process Communication), network, time, terminals

What’s the application / kernel interface?

-

“System calls”

-

Examples, in C, from UNIX (e.g. Linux, macOS, FreeBSD):

fd = open("out", 1); write(fd, "hello\n", 6); pid = fork(); -

These look like function calls but they aren’t

System Calls

| 函数名 | 功能描述 |

|---|---|

int fork() |

创建一个进程,返回子进程的 PID。 |

int exit(int status) |

终止当前进程,status 返回给 wait(),不返回。 |

int wait(int *status) |

等待子进程退出,退出状态存入 *status,返回子进程的 PID。 |

int kill(int pid) |

终止进程 PID。返回 0 或 -1(表示错误)。 |

int getpid() |

返回当前进程的 PID。 |

int sleep(int n) |

暂停 n 个时钟周期。 |

int exec(char *file, char *argv[]) |

加载并执行文件 file,传入参数 argv[],仅在发生错误时返回。 |

char *sbrk(int n) |

增加 n 字节的进程内存,返回新内存的起始地址。 |

int open(char *file, int flags) |

打开文件,flags 指示读/写模式,返回文件描述符。 |

int write(int fd, char *buf, int n) |

从 buf 中向文件描述符 fd 写入 n 字节,返回写入的字节数。 |

int read(int fd, char *buf, int n) |

从文件描述符 fd 中读取 n 字节到 buf,返回读取的字节数或 0(文件结束)。 |

int close(int fd) |

关闭文件描述符 fd。 |

int dup(int fd) |

返回一个新的文件描述符,指向与 fd 相同的文件。 |

int pipe(int p[]) |

创建一个管道,将读/写文件描述符放入 p[0] 和 p[1]。 |

int chdir(char *dir) |

更改当前目录为 dir。 |

int mkdir(char *dir) |

创建一个新目录 dir。 |

int mknod(char *file, int, int) |

创建一个设备文件。 |

int fstat(int fd, struct stat *st) |

将关于打开文件的信息放入 *st。 |

int stat(char *file, struct stat *st) |

将关于文件 file 的信息放入 *st。 |

int link(char *file1, char *file2) |

为文件 file1 创建另一个名称 file2。 |

int unlink(char *file) |

删除文件 file。 |

Why is O/S design + implementation hard and interesting?

-

unforgiving environment: quirky h/w, hard to debug

-

many design tensions:

- efficient vs abstract / portable / general-purpose

- powerful vs simple interfaces

- flexible vs secure

-

features interact:

fd = open(); fork() -

uses are varied: laptops, smart-phones, cloud, virtual machines, embedded

-

evolving hardware: NVRAM, multi-core, fast networks

-

You’ll be glad you took this course if you…

- care about what goes on under the hood

- like infrastructure

- need to track down bugs or security problems

- care about high performance

Class structure

-

Online course information: https://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.S081/2020 – schedule, assignments, labs Piazza – announcements, discussion, lab help

-

Lectures

- O/S ideas

- case study of xv6, a small O/S, via code and xv6 book

- lab background

- O/S papers

- submit a question about each reading, before lecture.

-

Labs: The point: hands-on experience Mostly one week each. Three kinds: Systems programming (due next week…) O/S primitives, e.g. thread switching. O/S kernel extensions to xv6, e.g. network. Use piazza to ask/answer lab questions. Discussion is great, but please do not look at others’ solutions!

-

Grading: 70% labs, based on tests (the same tests you run). 20% lab check-off meetings: we’ll ask you about randomly-selected labs. 10% home-work and class/piazza discussion. No exams, no quizzes. Note that most of the grade is from labs. Start them early!

Introduction to UNIX system calls

- I’ll show some examples, and run them on xv6. xv6 has similar structure to UNIX systems such as Linux. but much simpler – you’ll be able to digest all of xv6 accompanying book explains how xv6 works, and why

Why UNIX?

open source, well documented, clean design, widely used studying xv6 will help if you ever need to look inside Linux xv6 has two roles in 6.S081: example of core functions: virtual memory, multi-core, interrupts, &c starting point for most of the labs xv6 runs on RISC-V, as in current 6.004 you’ll run xv6 under the qemu machine emulator

Example: copy.c, copy input to output

read bytes from input, write them to the output

$ copy

copy.c is written in C

Kernighan and Ritchie (K&R) book is good for learning C

you can find these example programs via the schedule on the web site

copy.c

// copy.c: 复制输入到输出

#include "kernel/types.h" // 包含系统调用相关的类型定义

#include "user/user.h" // 包含用户态函数的声明(如 read, write, exit)

int

main()

{

char buf[64]; // 定义一个缓冲区,用于存储读取的数据

// 无限循环,直到读取到文件结束标志或出现错误

while(1){

// 从标准输入(文件描述符 0)中读取数据到 buf 中

int n = read(0, buf, sizeof(buf));

// 如果读取到的数据量小于等于 0,则表示输入结束或发生了错误

if(n <= 0)

break; // 退出循环

// 将读取的数据写入标准输出(文件描述符 1)

write(1, buf, n);

}

// 正常退出程序

exit(0);

}

read() and write() are system calls

first read()/write() argument is a "file descriptor" (fd)

passed to kernel to tell it which “open file” to read/write

must previously have been opened

an FD connects to a file/device/socket/&c

a process can open many files, have many FDs

UNIX convention: fd 0 is “standard input”, 1 is “standard output”

second read() argument is a pointer to some memory into which to read

third argument is the maximum number of bytes to read read() may read less, but not more return value: number of bytes actually read, or -1 for error

note: copy.c does not care about the format of the data

UNIX I/O is 8-bit bytes

interpretation is application-specific, e.g. database records, C source, &c

Where do file descriptors come from?

-

example: open.c, create a file

$ open$ cat output.txt

open() creates a file, returns a file descriptor (or -1 for error)

FD is a small integer

FD indexes into a per-process table maintained by kernel

[user/kernel diagram]

different processes have different FD name-spaces

i.e. FD 1 often means different things to different processes

these examples ignore errors – don’t be this sloppy!

Figure 1.2 in the xv6 book lists system call arguments/return

or look at UNIX man pages, e.g. “man 2 open”

What happens when a program calls a system call like open()?

looks like a function call, but it’s actually a special instruction

hardware saves some user registers

hardware increases privilege level

hardware jumps to a known “entry point” in the kernel

now running C code in the kernel

kernel calls system call implementation

open() looks up name in file system

it might wait for the disk

it updates kernel data structures (cache, FD table)

restore user registers

reduce privilege level

jump back to calling point in the program, which resumes

we’ll see more detail later in the course

-

I’ve been typing to UNIX’s command-line interface, the shell. the shell prints the “$” prompts. the shell lets you run UNIX command-line utilities useful for system management, messing with files, development, scripting

$ ls$ ls > out$ grep x < outUNIX supports other styles of interaction too

window systems,GUIs,servers,routers, &c. but time-sharing via the shell was the original focus of UNIX. we can exercise many system calls via the shell. -

example:

fork.c, create a new process

the shell creates a new process for each command you type, e.g. for

$ echo hello

the fork() system call creates a new process

$ fork

the kernel makes a copy of the calling process

instructions, data, registers, file descriptors, current directory

“parent” and “child” processes

only difference: fork() returns a pid in parent, 0 in child

a pid (process ID) is an integer, kernel gives each process a different pid

thus:

fork.c’s “fork() returned” executes in both processes

the “if(pid == 0)” allows code to distinguish

ok, fork lets us create a new process

how can we run a program in that process?

-

example:

exec.c, replace calling process with an executable file how does the shell run a program, e.g.$ echo a b ca program is stored in a file: instructions and initial memory created by the compiler and linker so there’s a file called echo, containing instructions

$ execexec()replaces current process with an executable file discards instruction and data memory loads instructions and memory from the file preserves file descriptorsexec(filename, argument-array)argument-array holds command-line arguments; exec passes to main() cat user/echo.c echo.c shows how a program looks at its command-line arguments -

example: forkexec.c,

fork()a new process, exec() a program$ forkexecforkexec.c contains a common UNIX idiom:

fork(): a child processexec(): a command in the child parent wait()s for child to finish the shell does fork/exec/wait for every command you type afterwait(), the shell prints the next prompt to run in the background – & – the shell skips thewait()exit(status)->wait(&status)status convention: 0 = success, 1 = command encountered an error note: thefork()copies, butexec()discards the copied memory this may seem wasteful you’ll transparently eliminate the copy in the “copy-on-write” lab

fork 和 exec 的区别

fork 用于创建新进程,父子进程并发执行。

exec 用于在现有进程中加载并运行新程序。

fork 系统调用

- 功能:

fork用于创建一个新进程,称为子进程。子进程是通过复制当前进程(父进程)的地址空间创建的,因此子进程和父进程几乎完全相同,拥有相同的代码、数据和打开的文件描述符。 - 执行结果:

- 父进程调用

fork后,返回值是子进程的 PID。 - 子进程从

fork返回时,返回值是 0。

- 父进程调用

- 特点:

- 子进程是父进程的几乎精确副本,包括文件描述符、变量、代码段等,但其 PID(进程 ID)不同。

- 并发执行:

fork之后,父进程和子进程可以并发执行各自的代码。 - 多次返回:

fork会返回两次,一次在父进程中,一次在子进程中。

exec 系统调用

- 功能:

exec用于替换当前进程的代码和数据段,加载一个新程序并执行该程序。当exec被调用时,当前进程的所有内容(如代码、数据、堆栈)都被新程序替换,但进程的 PID 不变。 - 执行结果:

exec不返回,除非调用失败。成功调用exec后,旧的程序代码完全被新程序替换。- 文件描述符不会被关闭(除非设置了

close-on-exec标志)。

- 特点:

exec只会改变进程的执行代码,不会创建新的进程。- 新程序继承了调用进程的 PID 和文件描述符,但原有的内存数据、堆栈、代码等都会被新程序替换掉。

-

example:

redirect.c, redirect the output of a command what does the shell do for this?$ echo hello > outanswer: fork, change FD 1 in child, exec echo

$ redirect$ cat output.txtnote:

open()always chooses lowest unused FD; 1 due toclose(1). fork, FDs, and exec interact nicely to implement I/O redirection separate fork-then-exec give child a chance to change FDs before exec FDs provide indirection commands just use FDs 0 and 1, don’t have to know where they go exec preserves the FDs that sh set up thus: only sh has to know about I/O redirection, not each program

It’s worth asking “why” about design decisions:

Why these I/O and process abstractions? Why not something else? Why provide a file system? Why not let programs use the disk their own way? Why FDs? Why not pass a filename to write()? Why are files streams of bytes, not disk blocks or formatted records? Why not combine fork() and exec()? The UNIX design works well, but we will see other designs!

-

example: pipe1.c, communicate through a pipe how does the shell implement

$ ls | grep x$ pipe1an FD can refer to a “pipe”, as well as a file the pipe() system call creates two FDs read from the first FD write to the second FD the kernel maintains a buffer for each pipe [u/k diagram]

write()appends to the bufferread()waits until there is data -

example: pipe2.c, communicate between processes pipes combine well with fork() to implement ls | grep x shell creates a pipe, then forks (twice), then connects ls’s FD 1 to pipe’s write FD, and grep’s FD 0 to the pipe [diagram]

$ pipe2 -- a simplified versionpipes are a separate abstraction, but combine well w/ fork()

-

example: list.c, list files in a directory how does ls get a list of the files in a directory? you can open a directory and read it -> file names “.” is a pseudo-name for a process’s current directory see ls.c for more details

Summary

- We’ve looked at UNIX’s I/O, file system, and process abstractions.

- The interfaces are simple – just integers and I/O buffers.

- The abstractions combine well, e.g. for I/O redirection.

You’ll use these system calls in the first lab, due next week.

Code

Pipes

int pipeFd[2]; // 管道文件描述符数组,pipeFd[0]为读取端,pipeFd[1]为写入端

char *arguments[2]; // 存储传递给exec的参数

int main() {

// 设置要执行的命令和参数

arguments[0] = "wc"; // 将 "wc" 命令作为参数传递给exec,用于统计输入的行、单词和字符数

arguments[1] = 0; // 以NULL表示参数结束

// 创建管道

pipe(pipeFd); // pipeFd[0]用于读取,pipeFd[1]用于写入

// 创建子进程

if(fork() == 0) { // 子进程代码,fork()返回0表示当前是子进程

close(0); // 关闭标准输入(文件描述符0)

dup(pipeFd[0]); // 将管道的读取端复制到文件描述符0,使标准输入重定向到管道的读取端

close(pipeFd[0]); // 关闭管道的读取端,已重定向到标准输入,不再需要

close(pipeFd[1]); // 关闭管道的写入端,子进程不负责写入数据

exec("/bin/wc", arguments); // 执行wc命令,读取标准输入(从管道中读取),计算行、单词和字符数

} else { // 父进程代码

close(pipeFd[0]); // 关闭管道的读取端,父进程不负责读取数据

// 向管道写入数据

write(pipeFd[1], "hello world\n", 12); // 将 "hello world\n" 写入管道,供子进程读取

close(pipeFd[1]); // 关闭管道的写入端,表示数据写入完成

}

return 0;

}

cat.c

#include "kernel/types.h" // 包含系统调用相关的类型定义

#include "kernel/stat.h" // 包含文件状态相关的定义

#include "user/user.h" // 包含用户态函数的声明(如 read, write, open, close, fprintf, exit)

char buf[512]; // 定义一个缓冲区,用于存储读取的数据

// 函数:cat

// 参数:int fd - 文件描述符

// 功能:从文件描述符 fd 中读取数据,并将其写入标准输出(文件描述符 1)

void

cat(int fd)

{

int n;

// 从文件描述符 fd 中读取数据到 buf 中,读取的字节数存储在 n 中

while((n = read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf))) > 0) {

// 将读取的数据写入标准输出

if (write(1, buf, n) != n) {

// 如果写入的字节数不等于读取的字节数,报告写入错误

fprintf(2, "cat: write error\n");

exit(1);

}

}

// 如果读取过程中出现错误,报告读取错误并退出

if(n < 0){

fprintf(2, "cat: read error\n");

exit(1);

}

}

// 主函数

int

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int fd, i;

// 如果没有提供文件参数,默认读取标准输入(文件描述符 0)

if(argc <= 1){

cat(0);

exit(0);

}

// 遍历命令行参数中的文件名

for(i = 1; i < argc; i++){

// 打开文件,获取文件描述符

if((fd = open(argv[i], 0)) < 0){

// 如果文件无法打开,报告错误并退出

fprintf(2, "cat: cannot open %s\n", argv[i]);

exit(1);

}

// 调用 cat 函数,将文件内容输出到标准输出

cat(fd);

// 关闭文件描述符

close(fd);

}

// 正常退出

exit(0);

}

echo.c

#include "kernel/types.h" // 包含系统调用相关的类型定义

#include "kernel/stat.h" // 包含文件状态相关的定义

#include "user/user.h" // 包含用户态函数的声明(如 write, exit, strlen)

int

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i;

// 遍历命令行参数,从第一个参数(argv[1])开始

for(i = 1; i < argc; i++){

// 将当前参数 argv[i] 写入标准输出(文件描述符 1)

write(1, argv[i], strlen(argv[i]));

// 如果不是最后一个参数,在其后写入一个空格

if(i + 1 < argc){

write(1, " ", 1);

} else {

// 如果是最后一个参数,在其后写入一个换行符

write(1, "\n", 1);

}

}

// 正常退出程序

exit(0);

}

forktest.c

// 测试 fork 是否能在进程表满时优雅地失败。

// 这个程序是一个小的可执行文件,用于填充进程表以测试 fork 的行为。

#include "kernel/types.h" // 包含系统调用相关的类型定义

#include "kernel/stat.h" // 包含文件状态相关的定义

#include "user/user.h" // 包含用户态函数的声明(如 write, exit, fork, wait, strlen)

#define N 1000 // 定义测试的 fork 最大次数

// 函数:print

// 参数:const char *s - 要输出的字符串

// 功能:将字符串 s 写入标准输出(文件描述符 1)

void

print(const char *s)

{

write(1, s, strlen(s)); // 使用 write 系统调用将字符串写入标准输出

}

// 函数:forktest

// 功能:测试 fork 系统调用的行为,特别是在进程表满时

void

forktest(void)

{

int n, pid;

// 输出开始测试的信息

print("fork test\n");

// 循环尝试创建 N 个子进程

for(n = 0; n < N; n++){

pid = fork(); // 创建一个子进程

if(pid < 0)

break; // 如果 fork 失败,退出循环

if(pid == 0)

exit(0); // 子进程退出

}

// 如果成功创建了 N 个子进程,表示 fork 行为异常

if(n == N){

print("fork claimed to work N times!\n");

exit(1);

}

// 等待所有子进程结束

for(; n > 0; n--){

if(wait(0) < 0){ // 等待子进程结束

print("wait stopped early\n");

exit(1); // 如果 wait 失败,报告错误并退出

}

}

// 如果 wait 没有返回 -1,表示还有多余的子进程

if(wait(0) != -1){

print("wait got too many\n");

exit(1);

}

// 输出测试成功的信息

print("fork test OK\n");

}

// 主函数

int

main(void)

{

forktest(); // 执行 fork 测试

exit(0); // 正常退出程序

}

stressfs.c

// Demonstrate that moving the "acquire" in iderw after the loop that

// appends to the idequeue results in a race.

// For this to work, you should also add a spin within iderw's

// idequeue traversal loop. Adding the following demonstrated a panic

// after about 5 runs of stressfs in QEMU on a 2.1GHz CPU:

// for (i = 0; i < 40000; i++)

// asm volatile("");

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "kernel/stat.h"

#include "user/user.h"

#include "kernel/fs.h"

#include "kernel/fcntl.h"

int

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int fd, i;

char path[] = "stressfs0";

char data[512];

printf("stressfs starting\n");

memset(data, 'a', sizeof(data));

for(i = 0; i < 4; i++)

if(fork() > 0)

break;

printf("write %d\n", i);

path[8] += i;

fd = open(path, O_CREATE | O_RDWR);

for(i = 0; i < 20; i++)

// printf(fd, "%d\n", i);

write(fd, data, sizeof(data));

close(fd);

printf("read\n");

fd = open(path, O_RDONLY);

for (i = 0; i < 20; i++)

read(fd, data, sizeof(data));

close(fd);

wait(0);

exit(0);

}

Lab - Util

sleep (easy)

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "kernel/stat.h"

#include "user/user.h"

int

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if(argc != 2){

fprintf(2, "Usage: sleep [the times of ticks]...\n");

exit(1);

}

int times = atoi(argv[1]);

sleep(times);

exit(0);

}

pingpong (easy)

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "kernel/stat.h"

#include "user/user.h"

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if (argc > 1)

{

fprintf(2, "Usage: pingpong (without any parameters)\n");

exit(1);

}

int pipe_fd[2];

if (pipe(pipe_fd) < 0)

{

fprintf(2, "pipe error\n");

exit(1);

}

int pid = fork();

if (pid > 0)

{

// 父进程关闭管道的写端

close(pipe_fd[1]);

// 父进程等待子进程的信号

char buf[1];

read(pipe_fd[0], buf, 1);

pid = wait((int *)0);

printf("%d: received pong\n", getpid());

// 父进程关闭管道的读端

close(pipe_fd[0]);

}

else if (pid == 0)

{

// 子进程关闭管道的读端

close(pipe_fd[0]);

printf("%d: received ping\n", getpid());

// 子进程通过管道向父进程发送信号

write(pipe_fd[1], "x", 1);

// 子进程关闭管道的写端

close(pipe_fd[1]);

exit(0);

}

else

{

printf("fork error\n");

exit(1);

}

exit(0);

}

primes (moderate)/(hard)

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "kernel/stat.h"

#include "user/user.h"

void sieve(int p_left) {

int p_right[2];

int prime;

// 从左侧管道读取第一个数字

if (read(p_left, &prime, sizeof(int)) == 0) {

close(p_left);

exit(0);

}

// 输出该素数

printf("prime %d\n", prime);

// 创建一个新的管道

if (pipe(p_right) < 0) {

fprintf(2, "pipe error\n");

exit(1);

}

if (fork() == 0) {

// 子进程递归处理

close(p_right[1]);

sieve(p_right[0]);

} else {

// 父进程继续读取并筛选

close(p_right[0]);

int num;

while (read(p_left, &num, sizeof(int)) != 0) {

if (num % prime != 0) {

write(p_right[1], &num, sizeof(int));

}

}

// 关闭管道,等待子进程结束

close(p_left);

close(p_right[1]);

wait(0);

exit(0);

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int p[2];

if (pipe(p) < 0) {

fprintf(2, "pipe error\n");

exit(1);

}

if (fork() == 0) {

close(p[1]);

sieve(p[0]);

} else {

close(p[0]);

// 将 2 到 35 的数字写入管道

for (int i = 2; i <= 35; i++) {

write(p[1], &i, sizeof(int));

}

close(p[1]);

wait(0);

exit(0);

}

return 0;

}

find (moderate)

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "kernel/stat.h"

#include "user/user.h"

#include "kernel/fs.h"

#include "kernel/fcntl.h"

#define MAXBUF 512 // 定义缓冲区大小

/**

* find - 递归查找目录树中与指定文件名匹配的文件。

* @path: 要搜索的目录路径。

* @filename: 要查找的文件名。

*

* 该函数通过递归遍历目录树,打印出与指定文件名匹配的文件的路径。

* 它会忽略特殊目录项 `.` 和 `..` 以避免递归回到当前或父目录。

*/

void find(char *path, char *filename) {

char buf[512], *p;

int fd;

struct dirent de;

struct stat st;

// 打开指定的目录路径

if ((fd = open(path, 0)) < 0) {

fprintf(2, "find: cannot open %s\n", path);

return;

}

// 获取文件状态(例如确定是文件还是目录)

if (fstat(fd, &st) < 0) {

fprintf(2, "find: cannot stat %s\n", path);

close(fd);

return;

}

// 判断文件类型,处理不同的情况

switch (st.type) {

case T_FILE: // 如果是普通文件

// 检查文件名是否与目标文件名匹配

if (strcmp(path + strlen(path) - strlen(filename), filename) == 0) {

// 如果匹配,打印文件路径

printf("%s\n", path); // 注意这里每个匹配的文件都应该在新行打印

}

break;

case T_DIR: // 如果是目录

// 检查路径长度是否超出缓冲区大小

if (strlen(path) + 1 + DIRSIZ + 1 > sizeof(buf)) {

printf("find: path too long\n");

break;

}

// 将当前路径复制到缓冲区中

strcpy(buf, path);

p = buf + strlen(buf);

*p++ = '/';

// 读取目录中的每个目录项

while (read(fd, &de, sizeof(de)) == sizeof(de)) {

if (de.inum == 0)

continue; // 跳过无效的目录项

// 将目录项名称复制到路径缓冲区

memmove(p, de.name, DIRSIZ);

p[DIRSIZ] = 0;

// 忽略特殊目录项 `.` 和 `..`

if (strcmp(de.name, ".") == 0 || strcmp(de.name, "..") == 0)

continue;

// 递归调用 find 函数处理子目录或文件

find(buf, filename);

}

break;

}

// 关闭文件描述符以释放资源

close(fd);

}

/**

* main - 程序的入口点,解析命令行参数并调用 find 函数。

* @argc: 参数个数。

* @argv: 参数值数组。

*

* 该函数验证参数的正确性,并调用 find 函数开始递归查找。

*/

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// 检查命令行参数是否正确

if (argc < 3) {

// 如果参数不足,打印使用说明并退出

fprintf(2, "Usage: find <directory> <filename>\n");

exit(1);

}

// 调用 find 函数,开始查找文件

find(argv[1], argv[2]);

exit(0);

}

xargs (moderate)

#include "kernel/types.h"

#include "kernel/stat.h"

#include "user/user.h"

#define MAXARG 32 // 最大参数数量

#define MAXBUF 1024 // 最大输入缓冲区大小

// 从标准输入读取一行

int read_line(char *buf, int size)

{

int i = 0; // 当前字符索引

char c; // 存储读取的字符

// 从标准输入逐字符读取,直到遇到换行符或缓冲区已满

while (i < size - 1)

{

if (read(0, &c, 1) != 1)

{

return i; // 到达输入结束或发生错误

}

if (c == '\n')

{

break; // 遇到换行符,停止读取

}

buf[i++] = c; // 将读取的字符存入缓冲区

}

buf[i] = '\0'; // 在字符串末尾添加 null 终止符

return i;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if (argc < 2)

{

fprintf(2, "Usage: xargs command [initial-args]\n"); // 如果没有提供命令参数,输出用法提示

exit(1); // 退出程序

}

char buf[MAXBUF]; // 用于存储输入行的缓冲区

// 从标准输入读取每一行

while (read_line(buf, sizeof(buf)) > 0)

{

// 创建命令行参数数组

char *cmd_argv[MAXARG + 2]; // +2: 一个存放命令名,一个存放拼接后的参数

cmd_argv[0] = argv[1]; // 命令名称

int i;

// 复制用户提供的初始参数(如果有)

for (i = 1; i < argc - 1 && i < MAXARG; i++)

{

cmd_argv[i] = argv[i + 1];

}

// 将读取的行作为最后一个参数

cmd_argv[i++] = buf;

cmd_argv[i] = 0; // 参数列表以 null 终止

int pid = fork(); // 创建子进程

if (pid < 0)

{

fprintf(2, "xargs: fork failed\n"); // 如果创建子进程失败,输出错误信息

exit(1); // 退出程序

}

else if (pid == 0)

{

exec(cmd_argv[0], cmd_argv); // 执行命令

fprintf(2, "xargs: exec failed\n"); // 如果执行命令失败,输出错误信息

exit(1); // 退出子进程

}

else

{

// 父进程中

wait(0); // 等待子进程完成

}

}

exit(0); // 正常退出程序

}